Inside the High-Stakes AI Copyright Showdown

As lawsuits build, a core question emerges

Artificial intelligence companies and media creators are entering a decisive phase in a long-simmering dispute: can AI models legally train on copyrighted material scraped from the web without paying for licenses? Courts in the United States and Europe are now weighing claims from publishers, authors, and image libraries against developers of large language and image models. The outcomes could reshape how AI is built, what it costs, and who benefits.

At the center of the fight is a simple reality. Modern AI systems learn from vast collections of text, images, audio, and video. These datasets often include news articles, books, photos, and other works protected by copyright. Rights holders argue that wholesale copying to build commercial models violates the law. AI firms counter that the process is transformative and permitted under doctrines such as fair use in the United States.

What the cases argue

Major lawsuits filed since 2023 include claims by news organizations, individual authors, and stock photo agencies. The suits allege that developers copied protected works at scale to create models that now compete with the original content. Some plaintiffs say their material has even been reproduced verbatim by chatbots and image generators. Defendants, including leading AI labs and their partners, argue that training uses are different from consumption, and that the outputs are new, not mere copies.

Legal experts say U.S. courts are likely to focus on the four fair-use factors:

- Purpose and character: Is training transformative and for a different purpose, such as enabling statistical learning, or primarily commercial copying?

- Nature of the work: Are the inputs highly creative works or more factual content?

- Amount and substantiality: How much of each work was copied and was the “heart” of the work used?

- Market effect: Does the AI system substitute for the original or harm its markets?

One policy reference looms large. The U.S. Copyright Office has said, “When an AI technology determines the expressive elements of its output, the generated material is not the product of human authorship.” That line, from the Office’s 2023 guidance, does not decide the training question, but it underscores how human contribution has become a central legal test for outputs and, indirectly, for training practices.

Why it matters to the public

The stakes extend well beyond courtrooms. If judges rule that training requires permission and payment, AI development costs could rise. Smaller labs might struggle. Model performance could shift if datasets shrink. On the other hand, new licensing revenues could support journalism, independent creators, and image libraries at a time when digital advertising is volatile.

Consumers would feel the changes in multiple ways. Chatbots and creative tools might include more limited excerpts from news articles and books. Some features could sit behind paywalls to offset higher licensing fees. There may be clearer labels for AI-generated content, as policymakers and platforms push for content provenance to curb misinformation.

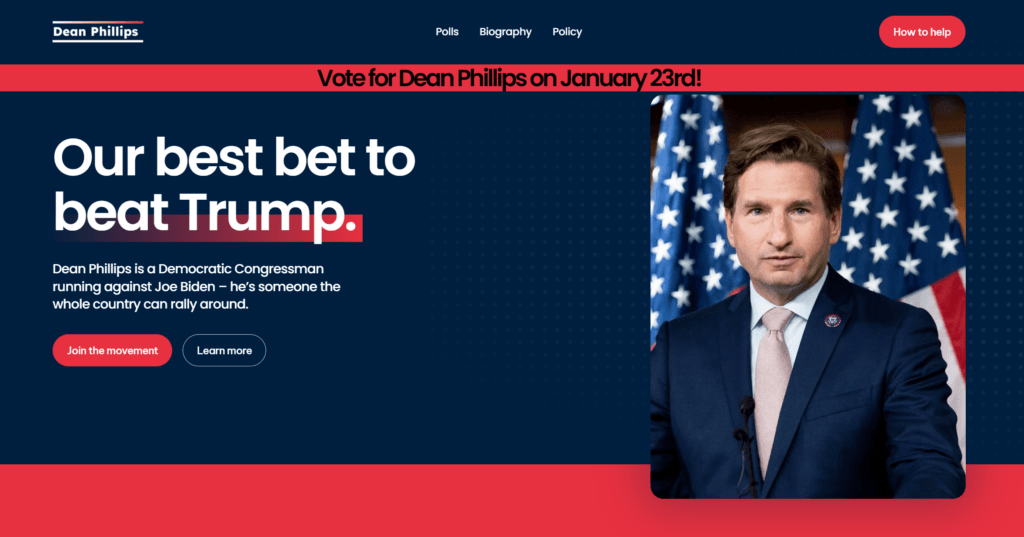

Licensing deals point to a middle path

Even as litigation proceeds, parts of the market are moving toward negotiated access. Some AI developers have struck agreements with publishers and platforms to license archives and provide attribution. These include deals with major news organizations and online communities in 2023 and 2024. The terms vary. In some cases, AI companies pay for access to content for training and display. In others, they license real-time content for answers and summaries.

Industry lawyers say these agreements could become templates. They may bundle several elements:

- Training licenses: Payment for historical archives and ongoing ingestion.

- Attribution and links: Source display in answers and previews to drive traffic back.

- Usage controls: Limits on reproduction, with takedown mechanisms.

- Data provenance: Records of what was used, when, and under what terms.

For creators, licensing offers clarity and revenue. For AI builders, it reduces uncertainty and reputational risk. Neither side gets everything it wants, but it allows products to ship while the law evolves.

Regulators are circling

Regulators are also shaping the debate. In the United States, the Federal Trade Commission has warned technology firms that existing consumer protection and competition laws apply to AI. As FTC Chair Lina Khan put it in 2023, “There is no AI exemption to the laws on the books.” Consumer groups are urging the agency to scrutinize how AI firms collect data, label outputs, and represent capabilities.

In Europe, the landmark EU AI Act establishes obligations for higher-risk systems and transparency requirements for general-purpose models. While the Act’s focus is not copyright, it intersects with the debate through documentation and disclosure. Model developers operating in the EU will have to publish certain details about training and risk management. That could make it easier for rights holders and regulators to audit practices.

Meanwhile, the U.S. Copyright Office has been studying the questions in depth, soliciting comments from creators, tech companies, academics, and the public in 2023 and 2024. The Office has not declared a blanket rule on training. Observers expect it to continue issuing guidance as courts decide concrete disputes.

What happens next

Most cases are in early or mid stages, and appeals are likely. Judges may split the issues: training as one question, and output reproduction as another. It is possible that courts find training on publicly available content to be fair use while penalizing verbatim regurgitation. It is also possible that courts draw lines between types of content, such as news versus highly creative fiction, or between open web material and paywalled archives.

Settlements are common in complex copyright cases. Parties could agree to licensing and technical safeguards, such as filters to prevent reproduction of protected passages and tools that respect opt-outs. If appellate courts issue broad rulings, Congress may face pressure to clarify the law, especially around text and data mining. Few expect a quick, universally binding answer.

How to read the tea leaves

Past precedent offers hints. In 2015, a U.S. appeals court held that Google’s book search project was fair use because it was transformative and did not replace the market for books. AI developers cite that case and others involving search indexing and text-and-data mining. Plaintiffs reply that generative systems are different because they can produce expressive text and images at scale, raising unique market harms.

The transformative question may be decisive. If a court sees training as enabling statistical analysis, like indexing, AI firms fare better. If a court sees it as industrial-scale copying to build products that compete with the originals, plaintiffs gain ground. The market-effect factor will also be pivotal, especially where chatbots display news or summarize paywalled articles.

What creators and companies can do now

- Audit data flows: Document what content is used for training, fine-tuning, and evaluation.

- Use content credentials: Adopt provenance standards to label AI-generated outputs and protect brand integrity.

- Offer clear policies: Provide opt-out mechanisms, respect robots.txt and site-level controls, and respond to takedown requests.

- Explore licenses: Consider collective licensing or direct deals that compensate rights holders and reduce legal risk.

- Harden safeguards: Deploy filters to prevent verbatim reproduction of protected text and images.

The AI sector is moving fast, but the law moves on its own timetable. For now, companies are trying to reduce risk through licensing and technical controls, while creators press their cases in court. The balance that emerges will influence not only who gets paid, but also how the next generation of AI is built.

This report is based on court filings, regulatory guidance, and industry announcements as of 2024. It is not legal advice.