EU’s AI Act Sets Global Rules: What Changes Now

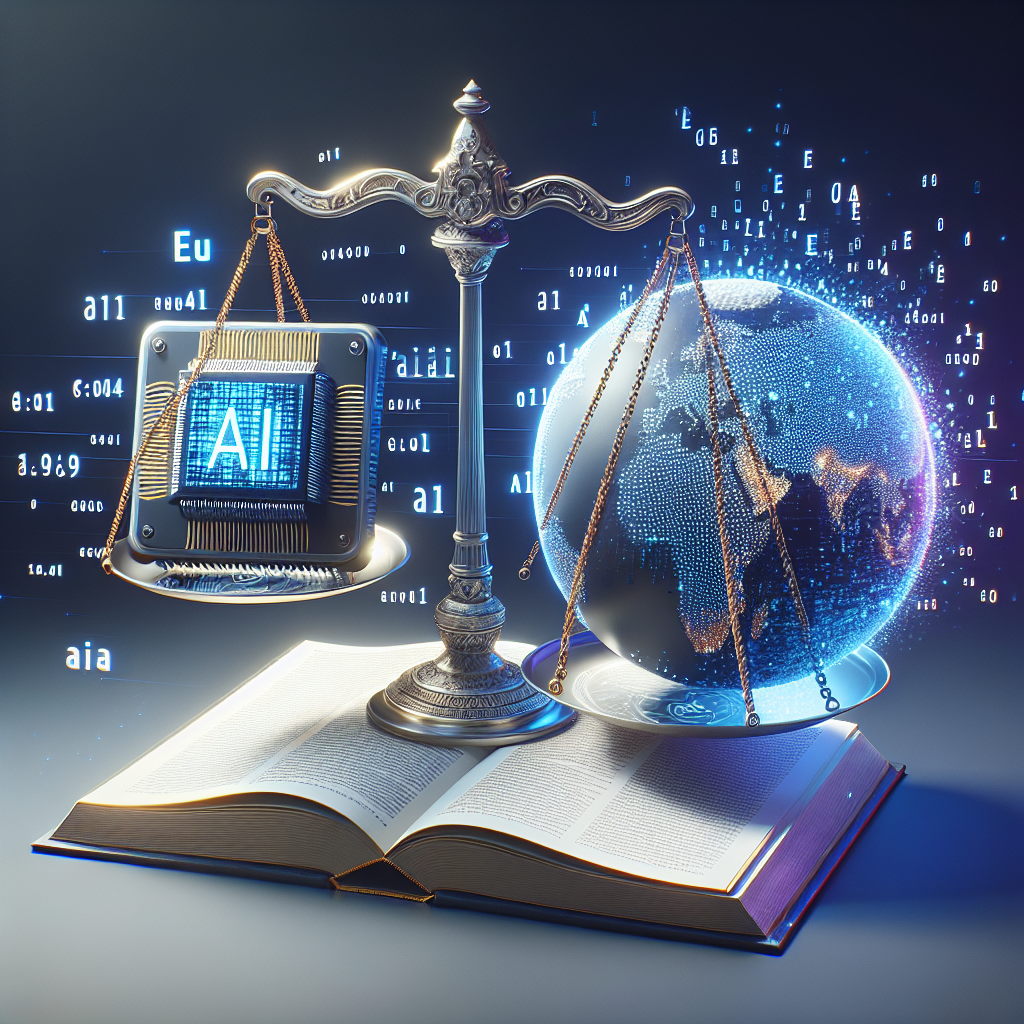

The European Union’s landmark Artificial Intelligence Act is moving from text to practice. Adopted in 2024 after years of negotiation, the law began taking effect in stages and will continue to roll out over the next two years. It is the first comprehensive attempt by a major regulator to set common, binding rules for AI across sectors. Supporters say it offers clarity and safeguards. Critics warn of gaps and compliance costs. Globally, technology firms and policymakers are watching closely.

What the law does

The AI Act uses a risk-based approach. The stricter the potential impact on safety or rights, the tighter the requirements. It defines several categories of AI use and sets different obligations for each.

- Banned practices: Systems deemed unacceptable are prohibited. These include AI that conducts government-run social scoring of individuals and some forms of real-time remote biometric identification in public spaces, with narrow exceptions defined by law enforcement needs.

- High-risk systems: Applications in areas such as critical infrastructure, education, employment, essential services, and law enforcement face strict rules. Providers must ensure data governance, technical documentation, transparency, human oversight, robustness, and cybersecurity.

- Limited-risk uses: Systems that interact with people must disclose that users are engaging with AI. Deepfakes and synthetic media require clear labeling so audiences understand content is generated or altered.

- General-purpose AI (GPAI): Developers of powerful foundation models must publish technical documentation, provide summaries of training data, and respect EU copyright rules. They must also support detection of AI-generated content.

The European Commission says the purpose is straightforward: “The AI Act aims to ensure that AI systems placed on the Union market are safe and respect fundamental rights”, according to its public Q&A materials. Enforcement lies with national authorities, coordinated at EU level.

Key dates and enforcement

The regulation entered into force in 2024. Its rules apply in phases to give organizations time to adapt:

- Within six months: Bans on prohibited practices begin to apply.

- Within 12 months: Transparency duties and certain obligations for general-purpose AI start to bite.

- Within 24 to 36 months: Most high-risk requirements become mandatory, including conformity assessments and post-market monitoring.

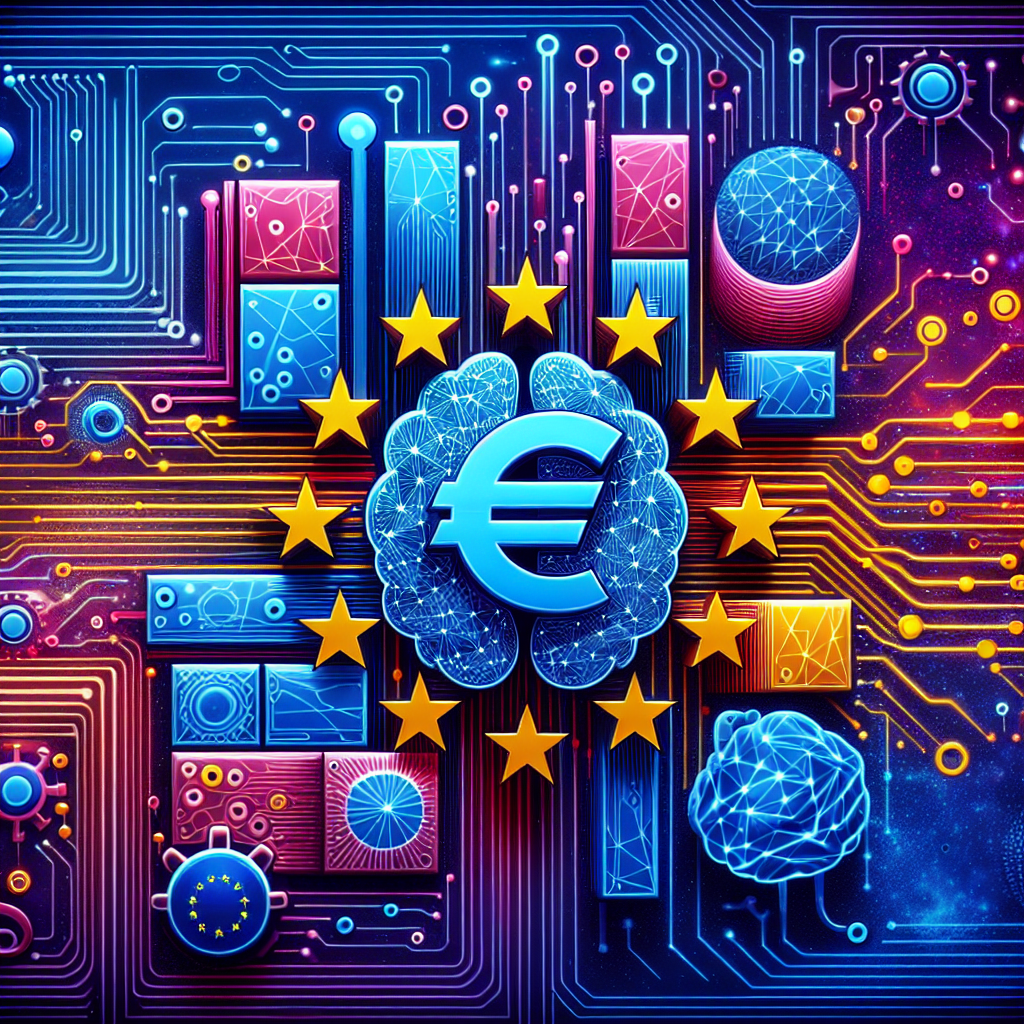

Penalties are steep. For the most serious violations, fines can reach up to €35 million or 7% of global annual turnover, whichever is higher, according to the final text. Lesser violations can still draw penalties in the millions. Member states will designate market surveillance and supervisory authorities. At EU level, the Commission has created an AI Office to oversee general-purpose AI and coordinate enforcement. A scientific panel will advise on fast-moving technical questions.

Why it matters globally

Brussels has a record of exporting standards. The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) reshaped privacy practices far beyond Europe. Many analysts expect a similar “Brussels effect” for AI. The EU’s rules could become a blueprint for companies that prefer one global compliance strategy rather than a patchwork of local fixes.

Thierry Breton, the European Commissioner for the Internal Market, highlighted the symbolic moment when the law passed: “The EU becomes the first continent to set clear rules for AI”, he said in a public post on X. For policymakers in Washington, London, and elsewhere, the EU’s move creates a new reference point. The United States has taken a mix of executive actions and agency guidance. The United Kingdom and several G7 countries are building testing regimes and voluntary codes. China has issued rules focused on recommendation algorithms and generative services. Few, however, match the breadth of the EU text.

What changes for companies and developers

For providers of high-risk systems, the law adds significant process. Firms must document model design and training data governance, run risk management, and ensure human oversight. They need incident reporting and post-market monitoring. Many will seek conformity assessments. Those that use third-party model providers will have to manage supply-chain risk and contractual duties.

General-purpose model makers face new transparency and copyright obligations. That includes sharing a training data summary and supporting watermarking or other content provenance tools. Downstream deployers remain responsible for the way they integrate and use these models. This division of responsibilities is intended to keep accountability close to the point of impact while bringing the largest model developers under a common baseline.

- Compliance programs: Companies are setting up cross-functional teams spanning legal, security, data science, and product. They are mapping AI use cases to risk categories.

- Model evaluations: Technical leaders are investing in robustness, red-teaming, and alignment testing. Documentation practices are expanding to satisfy audit needs.

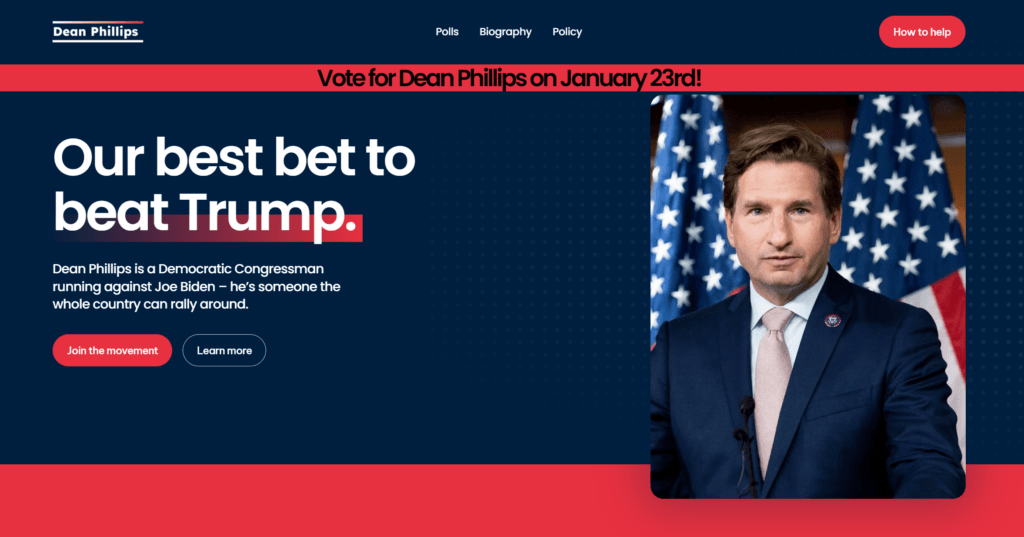

- Content provenance: Media and platforms are exploring labeling and detection tools to flag synthetic content, especially around elections and public safety.

Critiques and open questions

Rights advocates argue that the Act does not go far enough on biometric surveillance. They worry about broad exceptions and the real-world impact on civil liberties. Industry groups warn of over-compliance and administrative burden, especially for small and medium-sized enterprises. They want practical guidance so obligations are clear and consistent across member states.

There is also technical debate. Evaluating the capabilities and risks of frontier models is still an emerging science. Benchmarks change quickly, and adversarial testing is difficult to standardize. The EU’s scientific panel and international efforts, including work by national AI safety institutes and standards bodies, will be closely watched.

Another challenge is coordination. Many AI deployments intersect with existing laws, including product safety, consumer protection, nondiscrimination, and data protection. Companies will need to align their AI practices with GDPR and sector rules. Regulators must avoid conflicting guidance and ensure predictable enforcement.

What to watch next

- Secondary rules and guidance: The Commission and national authorities will publish guidelines, standards references, and templates. These will shape how the Act works in practice.

- Conformity assessment pathways: The role of notified bodies, testing labs, and audits will grow. Clear, feasible routes to compliance will be crucial.

- International alignment: Expect more cooperation on model testing, content provenance, and cybersecurity. Firms will push for interoperability between EU rules and frameworks from the U.S., U.K., and G7.

- Enforcement cases: Early actions by national authorities could set precedents on what counts as high risk, how to measure compliance, and how to calculate fines.

For now, the message is clear. The EU wants innovation, but with guardrails. The AI Act does not prescribe specific algorithms or ban research. It asks developers and deployers to know their systems, manage their risks, and explain their choices. That will not end debate about AI’s benefits and harms. But it creates a single rulebook for a market of more than 400 million people. In the global contest to shape AI, that alone is a major shift.