Europe Writes AI’s Rulebook: What Changes Now

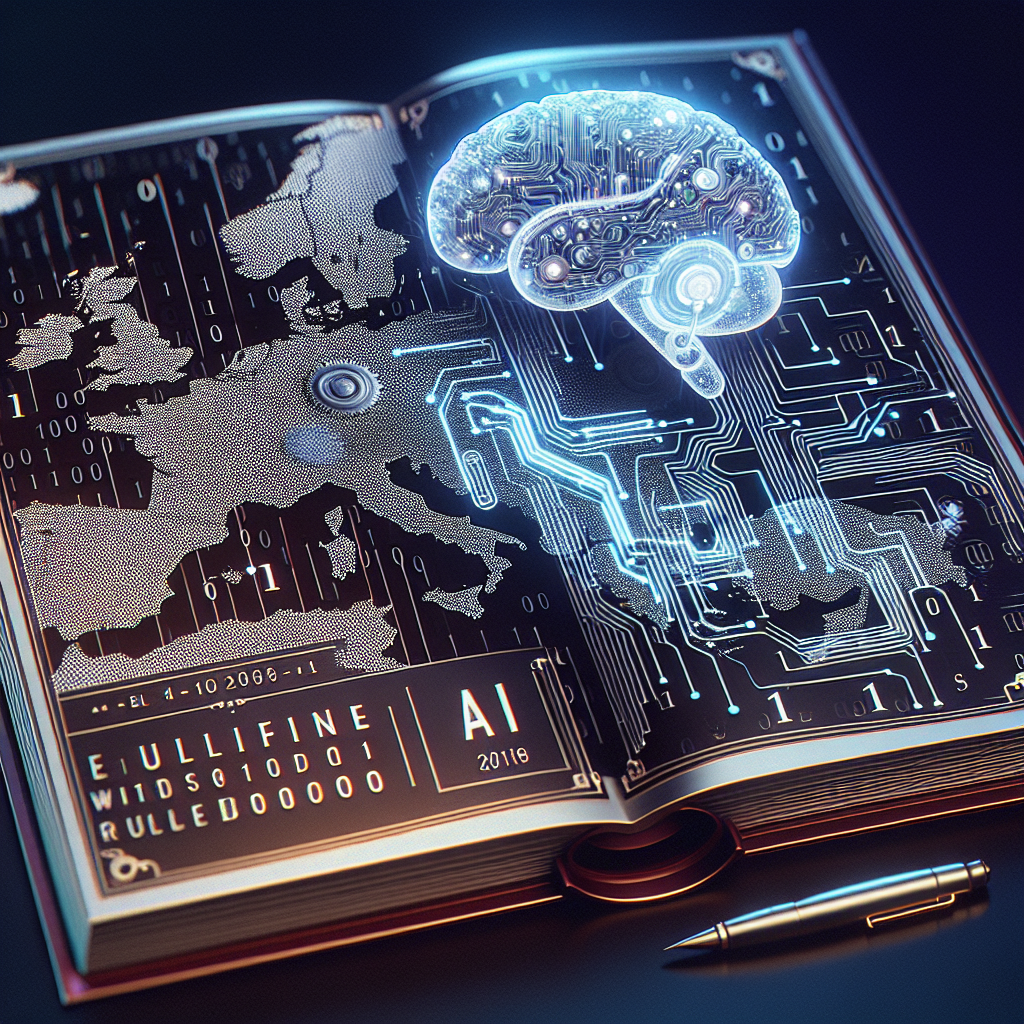

Brussels — Europe’s landmark Artificial Intelligence Act has moved from debate to implementation, putting companies around the world on notice that new, enforceable rules for AI are arriving soon. The law, formally approved in 2024 after years of negotiation, is the first comprehensive AI framework by a major economy. It aims to set clear guardrails for how AI can be designed and deployed, with penalties for violations and a phased timeline that stretches into 2026.

What the AI Act does

The EU AI Act takes a risk-based approach. It bans some uses outright, imposes strict controls on systems deemed high risk, and adds transparency duties for general-purpose models. The goal, policymakers say, is to protect fundamental rights while allowing innovation.

- Prohibited practices: The law bans AI for social scoring by public authorities, biometric categorization based on sensitive traits, and AI systems that manipulate behavior in ways likely to cause harm. It also places strict limits on real-time remote biometric identification in public spaces, allowing narrow exceptions defined in the law.

- High-risk systems: AI used in areas such as critical infrastructure, medical devices, employment, education, law enforcement, and migration will face mandatory risk management, data governance, human oversight, cybersecurity measures, and post-market monitoring.

- General-purpose AI (GPAI): Developers of powerful, general models must provide technical documentation, evaluate and mitigate systemic risks for the most capable models, and help downstream users comply. The European Commission’s new AI Office will supervise the largest models.

Sanctions are significant. For the gravest violations, fines can reach up to 7% of global annual turnover or tens of millions of euros, whichever is higher.

Who is affected

The law has an extraterritorial reach similar to GDPR. It applies to providers and users of AI systems that are placed on the EU market or whose outputs affect people in the EU, regardless of where the company is based. That means software firms in the United States, model labs in the UK, and hardware makers in Asia all need to assess how their AI products intersect with the new regime.

A wide range of organizations will be touched, including:

- Model developers building foundation models used by others.

- Enterprises applying AI in hiring, credit scoring, customer service, or safety-critical operations.

- Public authorities deploying AI for identification, benefits, or policing.

- Integrators and vendors bundling third-party AI into products.

Timeline and enforcement

The AI Act enters into force in stages. Bans on prohibited uses arrive first, roughly within months of the law’s publication. Obligations for general-purpose models follow next, while the bulk of high-risk requirements are expected to kick in over 2025–2026. National authorities will enforce the rules alongside the European Commission’s AI Office, and harmonized technical standards are being developed to give companies practical guidance.

For businesses, the staggered timetable is both an opportunity and a challenge. It creates time to prepare, but also a need to track evolving standards and guidance. The Commission plans to issue codes of practice, templates for documentation, and conformity assessment procedures, especially for high-risk sectors and advanced foundation models.

Industry reaction and global context

Industry leaders have long called for clear guardrails. In 2023 U.S. Senate testimony, OpenAI chief executive Sam Altman said, “Regulatory intervention by governments will be critical to mitigate the risks of increasingly powerful models.” Google’s Sundar Pichai wrote in 2020 that “AI is too important not to regulate.” Those views, once controversial in the tech sector, are now mainstream among large model developers and many enterprise users.

Governments also moved to coordinate. The UK-led Bletchley Declaration in late 2023 brought together major AI nations, calling for AI that is “safe, human-centric, trustworthy and responsible.” The United States, which does not have a comprehensive AI statute, has leaned on a 2023 Executive Order on AI and the NIST AI Risk Management Framework to guide federal use and encourage best practices. Japan and Canada are advancing their own frameworks. The G7’s Hiroshima Process continues to seek alignment on safety and transparency for general-purpose models.

Still, concerns persist. Startups warn that compliance costs may favor incumbents. Civil society groups argue the Act’s exceptions for law enforcement could be too broad. Industry advocates worry that stringent documentation rules could slow deployment in fast-moving fields. Policymakers counter that clear rules create trust, and trust supports adoption. The coming year will test both claims.

What businesses should do now

Experts say preparation beats retrofitting. Companies can reduce risk and cost by building compliance into development workflows. Practical steps include:

- Inventory your AI systems: Map where AI is used, who provides it, and who is affected. Identify potential high-risk uses early.

- Classify and document: For higher-risk use cases, start drafting technical documentation, data governance plans, and human oversight procedures aligned with emerging standards.

- Update contracts and procurement: Require vendors to supply model cards, data provenance information, and incident reporting terms. Clarify responsibilities for downstream compliance.

- Strengthen evaluations: Invest in testing and red-teaming, including bias, robustness, and privacy assessments. Record results for audits.

- Plan for transparency: Where the law requires it, design user notices and traceability features. Keep user experience clear and simple.

- Follow standards: Track EU harmonized standards and sector guidance. Align with frameworks such as NIST AI RMF to build common processes across regions.

What to watch next

The nuts and bolts now shift to regulators and standards bodies. The Commission’s AI Office will clarify how it will supervise general-purpose models and apply the “systemic risk” category to the most capable systems. European standards organizations will publish technical norms that operationalize the Act’s requirements. National authorities will ramp up capacity to inspect and enforce.

Global companies will look for convergence. If the EU’s approach becomes a de facto standard, developers may adopt one compliance program worldwide, as many did after GDPR. If rules diverge, firms could face a patchwork—slower and costlier to navigate.

AI is moving quickly. New multimodal systems that handle voice, image, and text are entering products from search to customer service. Chip advances promise more compute at lower cost. As the technology accelerates, Europe’s bet is that a clear rulebook can channel progress while reducing harm. The next 18 months will show whether that bet pays off—and how the rest of the world responds.