EU AI Act Sets Global Benchmark; Next: Enforcement

A landmark law enters a critical phase

Europe’s sweeping Artificial Intelligence law is now in force. The EU Artificial Intelligence Act, years in the making, aims to shape how AI is built and used. It sets rules at home. It also forces changes abroad. Any company that sells AI into the bloc will feel its impact. The next test is enforcement. Regulators must turn legal text into real checks. Companies must prove that their systems are safe, fair, and accountable.

The AI Act follows a risk-based approach. Uses judged to be an “unacceptable risk” are banned. Systems seen as “high-risk” must meet strict requirements. General-purpose and foundation models face transparency duties. Lawmakers say they want to protect rights and also support innovation.

What the law actually does

The Act sets clear rules for how AI may be used in Europe. It does not regulate science. It regulates the placing of AI on the market and its use. The core elements are simple in design and complex in practice.

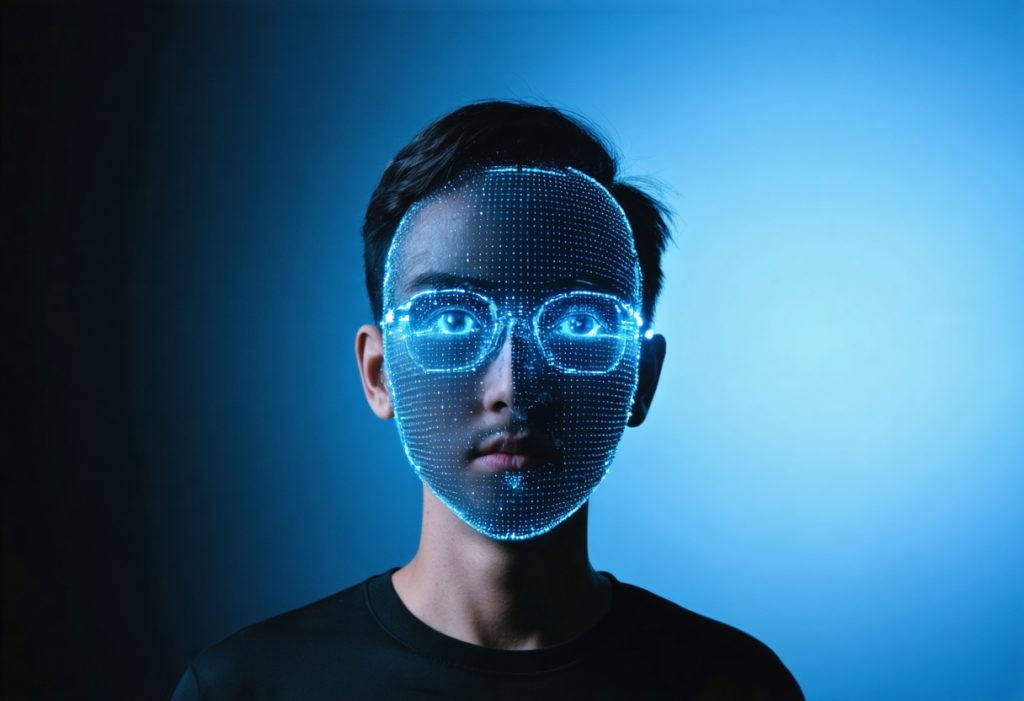

- Bans on certain practices: The law prohibits government “social scoring” of citizens. It restricts real-time remote biometric identification in public spaces, with narrow exceptions set by law. It bans biometric categorization that uses sensitive data, such as race or political beliefs. It also bans emotion recognition in workplaces and schools. These are labeled as “unacceptable risk”.

- Strict rules for high-risk AI: Tools used in critical areas are designated high-risk. These include systems for infrastructure, education, hiring, credit, essential services, law enforcement, migration, and justice. Providers must manage data quality, test performance, ensure human oversight, log activity, and prepare technical documentation.

- General-purpose AI obligations: Developers of general-purpose and foundation models must publish summaries of training data sources, document capabilities and limits, and respect copyright. Models with significant capabilities face extra duties due to potential systemic risk.

- Transparency for users: Providers must inform people when they interact with AI, see AI-generated content, or are subject to biometric identification. Synthetic media should be labeled.

The European Commission has set up an AI Office to coordinate enforcement and oversee general-purpose models. National regulators in each member state will supervise high-risk applications. Fines for breaches can be severe. The top tier can reach up to 7% of global annual turnover for the most serious violations.

How we got here

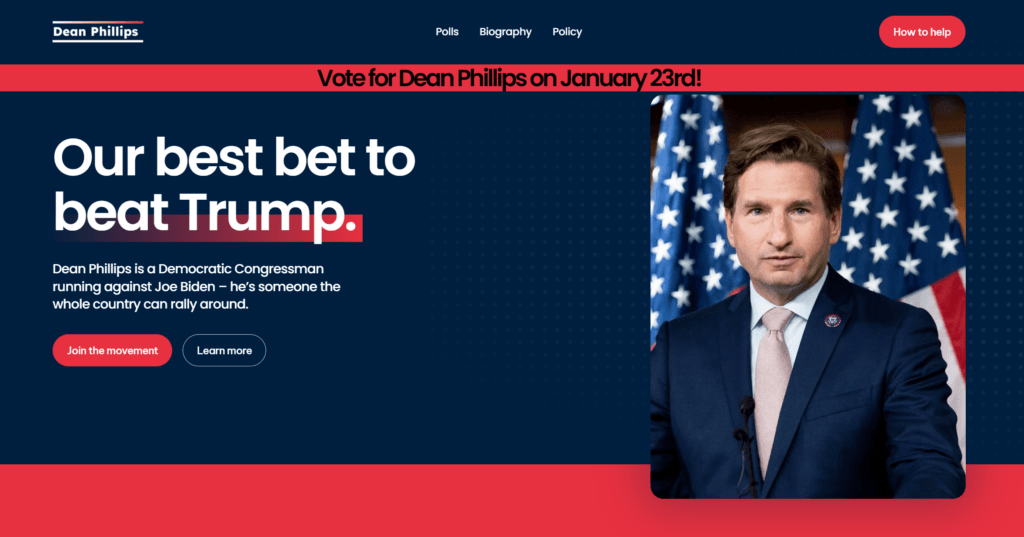

The European Commission proposed the AI Act in April 2021. EU governments and the European Parliament reached a political deal in late 2023. Formal approval followed in 2024, with the law entering into force after publication. The rollout is phased. Bans apply first. High-risk obligations and most duties take effect later. Sandboxes will help startups test systems under regulatory oversight.

Regulators say the goal is balance. They want to protect fundamental rights and safety. They also want to lower compliance burdens for small firms. The Act encourages codes of practice, standards, and guidance. It gives time for companies to adapt.

Voices and sources

The law’s text uses clear labels. It defines “unacceptable risk” and “high-risk” tiers. It names prohibited practices like “social scoring” and “biometric categorization” using sensitive data. These terms reflect concerns raised by civil society and data protection authorities.

The U.S. National Institute of Standards and Technology describes its voluntary framework this way: it is intended to “help organizations manage AI risks.” That is from the NIST AI Risk Management Framework published in 2023. The White House also issued an Executive Order on the “safe, secure, and trustworthy” development and use of AI in 2023. The UK has set out a “pro-innovation” approach led by sector regulators. These statements show a global trend. Governments want AI benefits. They also worry about harms.

What companies must do now

Firms using or building AI for the EU market face new due diligence. The tasks are concrete. They also require documentation that can be audited.

- Catalog your AI: Map AI systems and uses. Identify whether any use is prohibited or high-risk. Check whether a model is general-purpose.

- Upgrade data governance: Document datasets, sources, and licensing. Track bias risks and data quality checks.

- Strengthen testing: Run pre-deployment tests. Validate performance for intended use. Stress test under edge cases and shifts.

- Build human oversight: Define when and how people can intervene. Provide clear instructions and escalation paths.

- Improve documentation: Prepare technical files, risk assessments, and user instructions. Maintain logs and traceability.

- Monitor after launch: Set up post-market monitoring. Record incidents and report serious events to authorities when required.

- Label and disclose: Inform users about AI interactions. Mark AI-generated content where relevant.

General-purpose model providers should also publish summaries of training data sources and detail model capabilities and limits. They may be asked to assess downstream risks, support security testing, and cooperate with the EU AI Office.

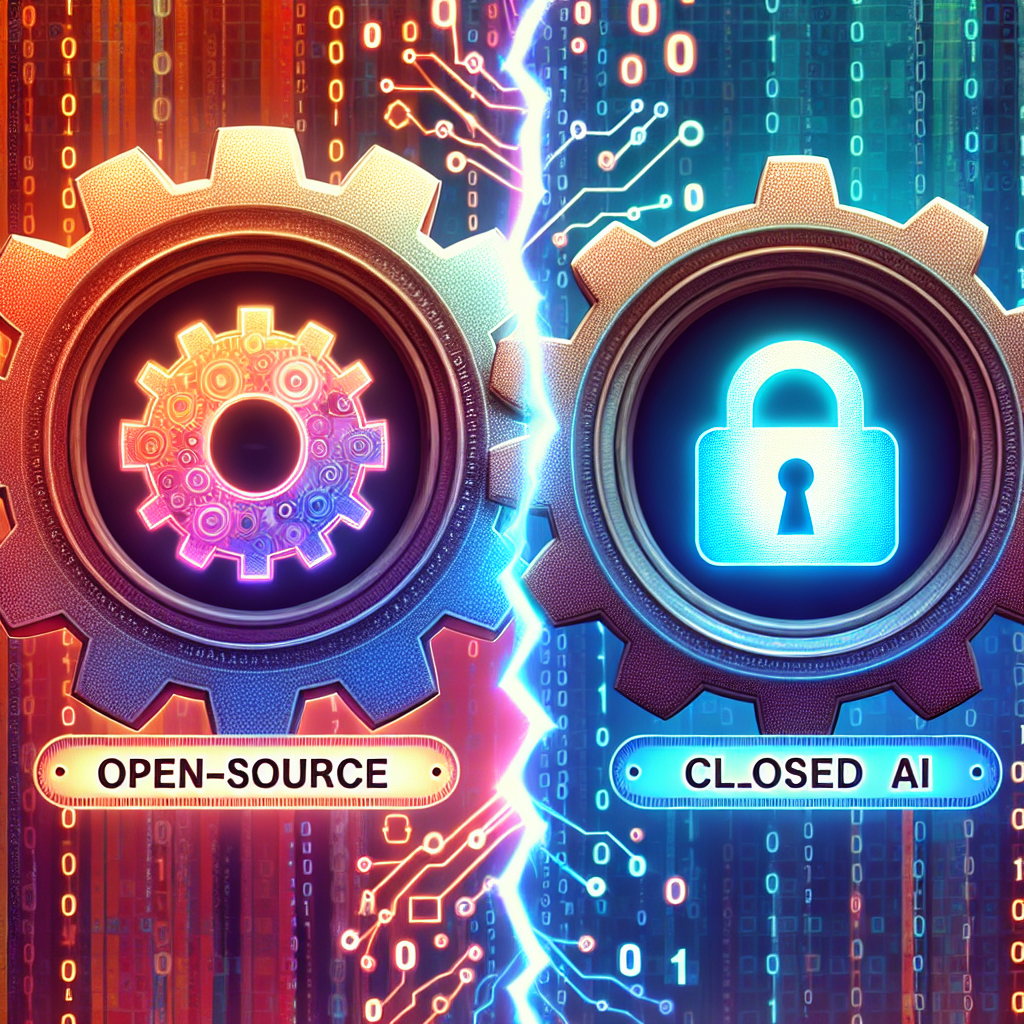

Supporters and critics weigh in

Rights groups welcome bans on invasive surveillance. They argue that some uses, if allowed, could chill free expression. Industry groups say the risk-based approach is better than blanket rules. But they worry about compliance costs and uncertainty for open-source models. Startups ask for clear guidance and workable templates.

Academic researchers warn that rules must stay flexible. AI systems change fast. Static requirements can lag behind practice. Standards bodies will play a key role. Harmonized European standards could translate legal goals into technical methods. That includes testing, robustness, data governance, and transparency.

Global context and spillover effects

The EU is not alone. The United States favors a mix of sector rules, federal procurement policies, and voluntary frameworks. NIST’s approach focuses on risk management, governance, and measurement science. The UK relies on existing regulators to apply AI principles in their domains. China has issued rules for recommendation algorithms, deepfakes, and generative AI services. Other countries are drafting national strategies and model policies.

EU rules tend to have global reach. This is the so-called Brussels effect. Firms that operate worldwide often align to the toughest market. That could spread documentation and testing norms far beyond Europe. It could also influence how model providers publish information about training data and capabilities.

Enforcement challenges ahead

The law’s success will hinge on capacity. National authorities must hire staff with technical skills. The EU AI Office must coordinate guidance and share best practices. Courts will clarify grey areas. Companies will seek answers on scope, definitions, and what evidence regulators will accept. Small firms will look for sandboxes, templates, and safe harbors.

There are also open debates. How should general-purpose model duties scale with capability? How should open-source developers be treated when others deploy their models in risky settings? What metrics are reliable for bias, robustness, and security? Some answers will come through standards and case law. Others will come from practice.

Why it matters

The AI Act tries to set guardrails without freezing progress. It applies known tools from product safety law to a fast-moving field. The bet is that rules will build trust. If people trust AI, they may use it more. If companies know the rules, they may invest more. The risks are real. So are the opportunities. The coming years will show whether a risk-based regime can keep up with the pace of change—and whether enforcement matches the ambition written into law.