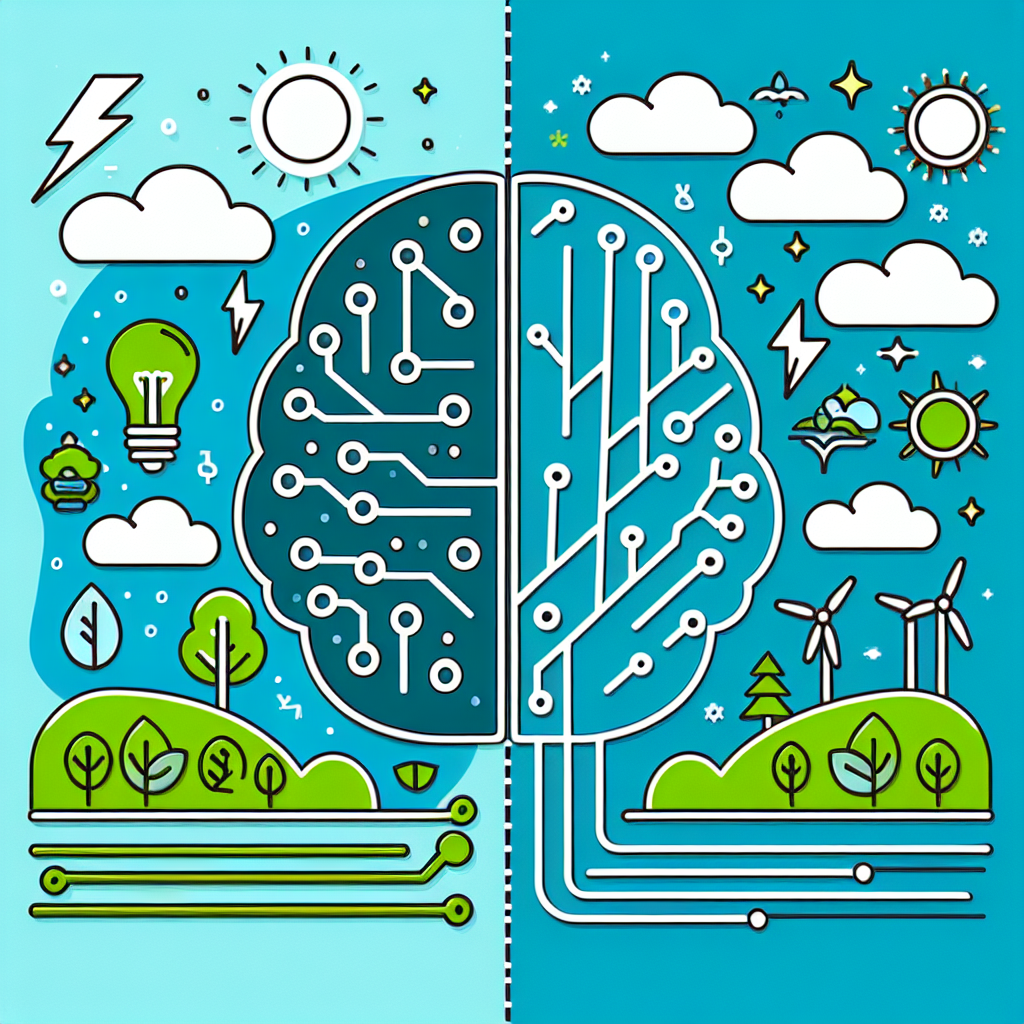

AI’s Power Problem: Can Computing Go Green?

Artificial intelligence is booming, and so is its energy use. As generative models move from labs to everyday products, the electricity and water required to run them are drawing scrutiny from regulators, utilities, and communities. Supporters say AI can accelerate scientific discovery and boost productivity. Critics warn the industry is outpacing infrastructure and environmental planning. The question facing policymakers and providers is simple: how to grow AI without overloading the grid or the planet.

The demand surge, by the numbers

The International Energy Agency (IEA) signaled the scale of the challenge in 2024. In a widely cited assessment, the agency said: "Electricity consumption from data centres, AI and cryptocurrencies could double by 2026." The warning reflects two pressures: energy-intensive training of large models and the spread of AI features into search, office apps, and customer service that run continuously once deployed.

Measuring the exact footprint is difficult. Providers disclose limited details for competitive and security reasons. Yet sustainability reports from major cloud companies have acknowledged rising power and water use as AI workloads expand. Training a single frontier model can draw as much electricity as thousands of homes over weeks. Keeping inference fast for millions of users brings its own load, concentrated in a handful of metro areas where data centers cluster near fiber and substations.

Why AI uses so much power

AI models learn by processing immense datasets using specialized chips. Training can run for weeks, iterating over billions of parameters. Inference—the answering of queries after training—is more efficient per request but happens constantly, at scale.

The hardware that enables this—graphics processing units (GPUs) and other accelerators—packs high performance into dense racks. That density pushes up electricity use and heat, which in turn requires cooling. Older sites rely on air cooling; newer designs turn to liquid cooling to move heat more efficiently. Either way, energy is lost as heat and water demand can rise in dry, hot regions if evaporative cooling is used.

Software matters as well. Algorithmic breakthroughs can reduce how many computations are needed to reach a given level of accuracy. Smaller, task-specific models can handle many jobs without the footprint of the largest systems. But many consumer-facing services still lean on big models for quality and flexibility, especially in their early iterations.

What industry is doing

Facing pressure from customers, investors, and local authorities, cloud providers and AI labs are pursuing a mix of technical and sourcing strategies. Common responses include:

- More efficient chips and servers. New accelerator generations promise more computations per watt. System designs cut idle energy and improve power distribution.

- Smarter code. Researchers optimize training recipes, prune parameters, and distill large models into lighter versions for production use.

- Advanced cooling. Liquid cooling and heat reuse reduce wasted energy. Some campuses pipe waste heat to nearby buildings.

- Clean power procurement. Long-term contracts with solar, wind, hydro, and nuclear projects aim to match or offset rising demand. Some firms experiment with on-site generation and storage.

- Load shifting. Moving flexible workloads to times or places with cleaner, cheaper electricity—when the sun shines or the wind blows—helps align AI cycles with the grid.

The industry also frames AI as part of the solution. Machine learning helps forecast wind and solar output, optimize battery dispatch, and detect leaks in power lines and pipelines. Those applications can cut emissions and improve reliability, though they do not erase AI’s own footprint.

Policymakers step in

Governments are shaping the field with new rules and standards. The European Union’s AI Act, approved in 2024, takes a risk-based approach and introduces transparency and safety obligations. While its core focus is on how AI is designed and used, it is likely to interact with energy and environmental law through reporting and compliance demands.

In the United States, a 2023 executive order called for "safe, secure, and trustworthy" AI, directing agencies to develop testing, reporting, and cybersecurity benchmarks. The National Institute of Standards and Technology has promoted risk management practices that include monitoring system performance over time—an approach that can encompass resource use as part of operational risk.

Local regulators and utilities are a central part of the story. Permitting for new data centers increasingly weighs grid capacity, water availability, and noise and traffic impacts. Some regions now require environmental impact assessments, heat-reuse plans, or commitments to procure clean power. Others court investment with tax incentives and fast-track approvals, seeking jobs and tax revenue.

Communities press for balance

Residents near fast-growing data center corridors have raised concerns about electricity reliability, rising rates, and water stress. Environmental groups warn that siting large facilities in drought-prone areas can exacerbate shortages, especially during heat waves. Industry groups counter that modern designs use less water per unit of computing and that operators can switch to water-free cooling on hot days.

Economists point to trade-offs. Data centers can anchor local tax bases and construction jobs. They also require transmission upgrades that take years. Consumer advocates argue for more transparency so ratepayers understand who benefits and who pays.

Many in the AI field acknowledge the stakes. Years before today’s surge, computer scientist Andrew Ng argued that "AI is the new electricity." The metaphor captures both promise and dependence: transformative potential tied to a vast physical system that must be planned, financed, and maintained.

What to watch next

- Better metrics. Standardized reporting on energy and water use per unit of compute would allow apples-to-apples comparisons across providers and models. Without common baselines, claims of efficiency are hard to verify.

- Grid upgrades. Transmission buildout and interconnection queues are bottlenecks in many countries. How quickly these improve will shape where and how fast AI capacity can grow.

- Clean firm power. Pairing variable renewables with storage, geothermal, hydro, or nuclear could help AI-heavy regions decarbonize while meeting peak demand. Procurement choices will influence emissions trajectories.

- Algorithmic efficiency. Continued progress in model architectures and compression can curb growth in compute needs. This is the fastest-moving lever the sector controls directly.

- Local guardrails. Expect more siting rules on water use, heat reuse, noise, and community benefits as municipalities respond to public pressure.

The bottom line

AI’s footprint is large and growing. The IEA’s warning highlights a near-term window in which power demand from data centers, AI, and crypto could double. That need not derail climate goals or strain grids if developers, utilities, and governments plan together and move quickly on efficiency and clean energy.

The path forward is not about choosing between innovation and sustainability. It is about aligning incentives and standards so that the next wave of compute is cleaner and more transparent than the last. That means candid reporting, smarter software, better chips, and infrastructure that keeps pace. It also means listening to the communities that host this growth.

The stakes are high, but so is the potential. With clear rules and engineering focus, AI can help modernize the energy system even as it draws on it. The outcome will depend on choices made now—about where to build, what to buy, and how to measure progress—before demand rises further.