AI’s New Rulebook: What Changes and Who’s Ready

Governments move from promises to enforcement

Rules for artificial intelligence are no longer an idea. They are arriving in stages, with real obligations, audits, and penalties. The European Union’s AI Act entered into force in 2024 and will apply in phases over the next few years. In the United States, agencies are tying federal funding and procurement to safety practices. Global standards bodies have published guidance that companies can use now. The result is a new era for AI governance. It is practical. It is measurable. And it will reshape how AI is built and deployed.

Why this matters now

The stakes are high. AI systems influence hiring, credit, health care, policing, and public information. Regulators want those systems to be safe, fair, and accountable. Business leaders want clear rules so they can invest with confidence. As EU Commissioner Thierry Breton said when lawmakers approved the bloc’s law in 2024, “Europe is now the first continent to set clear rules for AI.” That message is heard far beyond Europe.

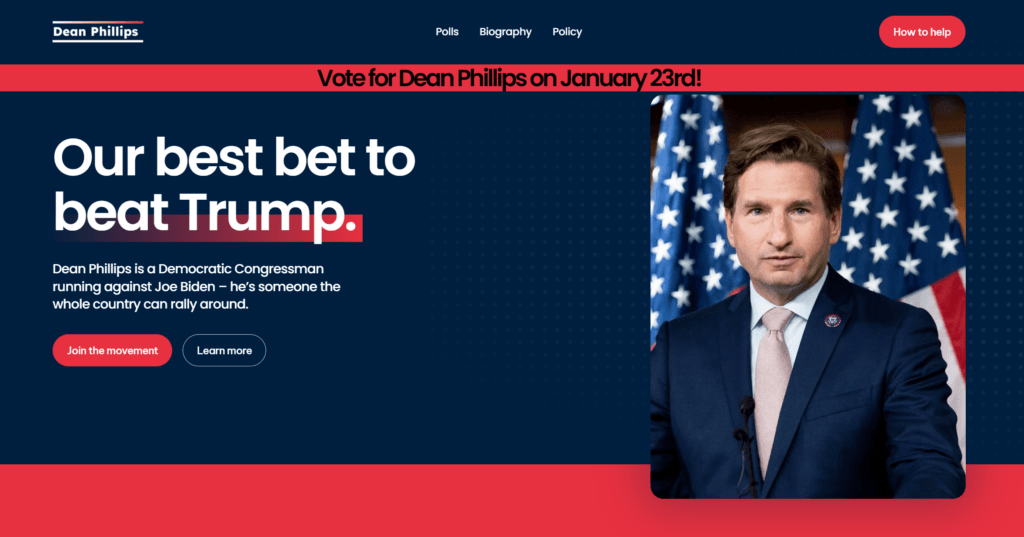

Industry voices also call for guardrails. OpenAI chief executive Sam Altman told the U.S. Senate in 2023, “We think that regulatory intervention by governments will be critical to mitigate the risks of increasingly powerful models.” The debate now is less about whether to regulate and more about how to make the rules work in practice.

What the EU AI Act will require

The EU AI Act uses a risk-based approach. It bans a small set of uses, sets strict duties for “high-risk” systems, and creates tailored obligations for general-purpose AI (GPAI), including large models. The law applies in stages over several years, with some prohibitions and transparency rules taking effect earlier than others.

- Bans (unacceptable risk): Social scoring by public authorities, certain types of biometric categorization using sensitive traits, and intrusive real-time biometric surveillance in public spaces, with narrow exceptions for law enforcement under strict conditions.

- High-risk systems: Tools used in critical areas such as education, employment, essential services, migration, law enforcement, and the administration of justice. Providers must implement risk management, data governance, human oversight, cybersecurity, and post-market monitoring. They will need conformity assessments and documentation before placing systems on the EU market.

- General-purpose AI: Model developers must share technical documentation, respect copyright rules, and provide information downstream so deployers can comply. The most capable models that pose “systemic risk” face additional duties, including model evaluations, incident reporting, and security measures.

National authorities will enforce the law. A new European AI Office will coordinate across borders. Fines can be significant, especially for banned uses and repeated violations. Many companies will use the next 12 to 36 months to build compliance programs, update contracts, and map their AI portfolios by risk level.

The U.S. approach: standards and procurement power

The United States is relying on guidance, existing laws, and federal purchasing to steer the market. The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) released the AI Risk Management Framework (AI RMF 1.0) in January 2023. NIST describes the framework as “intended to help organizations manage AI risks” through governance, mapping, measurement, and mitigation. It is voluntary, but agencies and companies are adopting it as a baseline.

The White House issued a sweeping executive order on AI in October 2023. It directed agencies to develop safety test protocols for advanced models, to guide watermarking and content provenance, and to assess impacts on privacy and civil rights. It also tied federal grants and contracts to stronger safeguards. Those steps do not create a single new AI law. But they do raise the bar for any company that wants to sell AI systems to the U.S. government or work on federally funded projects.

How companies are preparing

Companies are moving from principles to controls. The focus is on documentation, testing, and accountability. Many are standing up cross‑functional teams that include compliance, security, legal, data science, and product owners.

- Inventory and risk mapping: Listing AI systems in use or development. Classifying them by risk and use case.

- Data and model governance: Tracking training data sources, documentation, and licensing. Implementing evaluation pipelines, red‑team testing, and monitoring.

- Human oversight and UX: Designing clear user controls, escalation paths, and fail‑safes. Training staff on appropriate use.

- Supply‑chain diligence: Updating contracts with vendors and model providers. Requesting model cards, safety evaluations, and incident reporting commitments.

- Management systems: Adopting standards such as ISO/IEC 42001 (AI management systems) and ISO/IEC 23894 (AI risk management) to align with emerging regulation.

Startups worry about cost and speed. Larger firms worry about scale and legacy systems. Both groups seek clarity on how to classify use cases and how much testing is enough. Regulators say proportionality matters: higher risk means deeper controls.

Voices of caution and support

Rights groups welcome bans on abusive surveillance but warn about loopholes. They urge tighter limits on biometric use, stronger redress for people harmed by AI decisions, and more transparency for law enforcement deployments. Industry groups support clear definitions and harmonized standards. They caution against rules that could stifle open research or shut small developers out of the market. Academic experts point to systemic risks that cross borders, such as model proliferation and cyber misuse, and call for shared testing infrastructure.

There is broad agreement on some basics: transparency about capabilities and limits, robust security, and human review for high‑stakes decisions. The tough questions lie in the details, such as how to measure bias across contexts, how to verify content provenance at scale, and how to audit black‑box models without exposing trade secrets.

Global ripple effects

The EU’s timeline is already shaping international plans. Multinationals want a single set of controls that work across markets. Governments are coordinating through the G7’s Hiroshima AI Process, the OECD’s AI principles, and bilateral talks. The United Kingdom convened an AI Safety Summit in 2023 and launched a public evaluator program. Other countries are updating privacy laws and sector rules to cover automated decision‑making.

Standards bodies play a key role. ISO and IEC have released guidance on risk management, governance, and lifecycle controls. These documents help companies prepare for audits and simplify cross‑border compliance. They also give regulators a common language for enforcement.

What to watch next

- EU implementation guidance: Codes of practice for general‑purpose AI, templates for technical documentation, and sector‑specific notes for high‑risk uses.

- Model evaluations: Growth of independent testing, red‑team exercises, and benchmark suites for safety, robustness, and misuse resistance.

- Content provenance: Watermarking and metadata tools to label AI‑generated media, and how platforms adopt them.

- Copyright and data sourcing: Clarification of opt‑outs, licensing, and compensation models for training data.

- Enforcement actions: Early cases that define what counts as adequate testing, documentation, and oversight.

The direction is clear. AI developers and deployers will need to show their work: how they tested systems, what risks they found, and how they mitigated them. The goal is not to freeze innovation. It is to build trust, reduce harm, and give the public and regulators visibility into systems that have real impact on people’s lives.

As the regulatory era begins, one thing stands out. The organizations that treat compliance as an engineering discipline—not just a legal checkbox—will move fastest. They will also be the ones most ready when the next wave of rules arrives.