Europe’s AI Act: What Changes and What Comes Next

Europe sets a global marker for AI rules

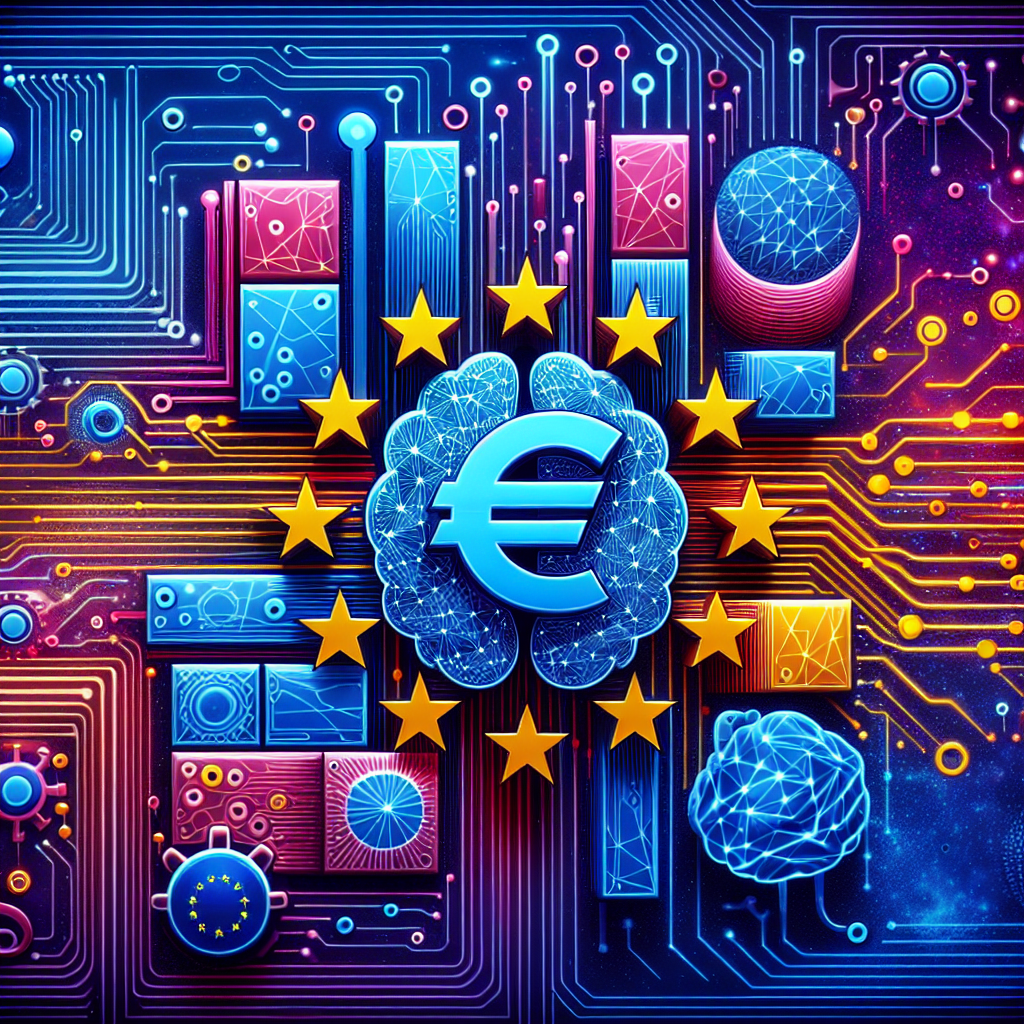

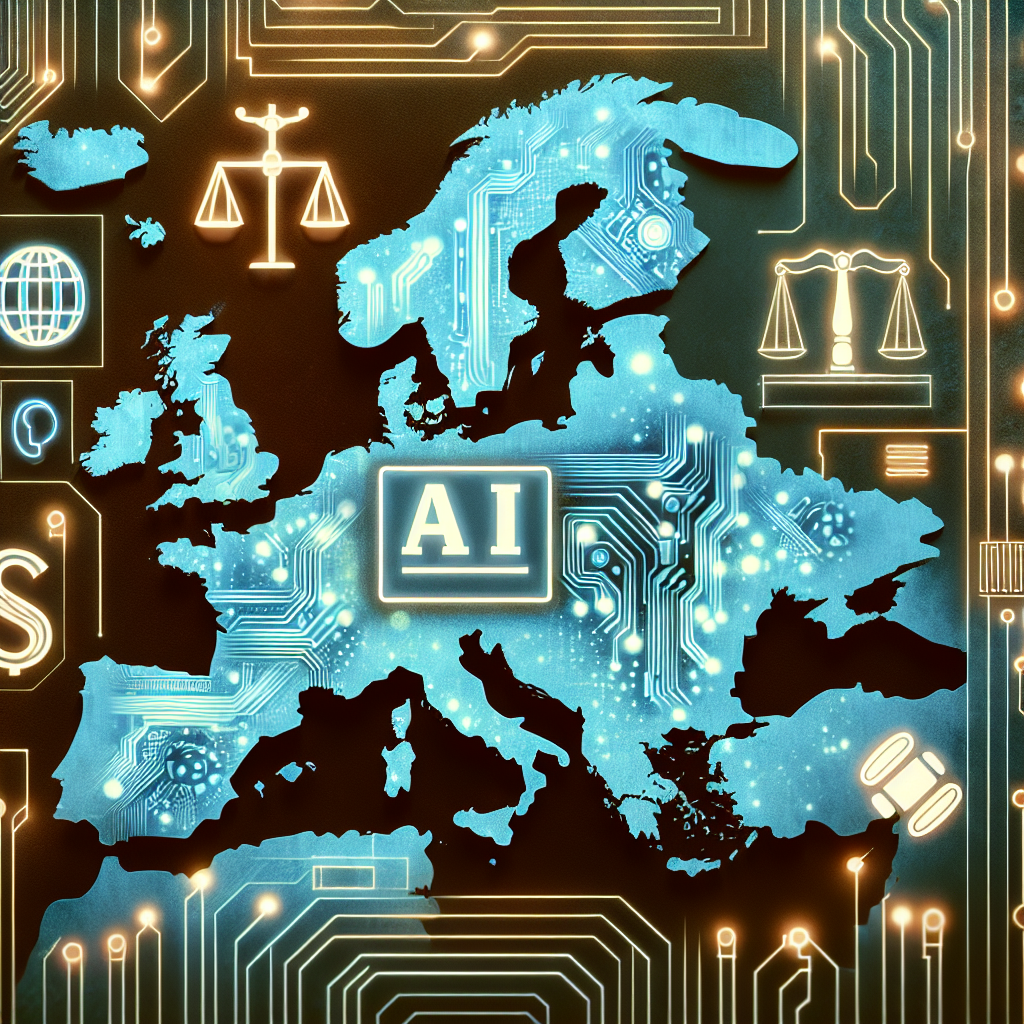

The European Union’s Artificial Intelligence Act has entered into force after final approval in 2024. It is the first comprehensive law aimed at governing artificial intelligence across a major economy. Regulators say the goal is to build trust and reduce harm without freezing innovation. The law takes a risk-based approach and applies in stages over the next several years.

In an official summary, the European Commission says the regulation seeks to ensure that AI systems used in the bloc are “safe and respect fundamental rights.” Supporters argue the framework could become a template for other countries. Critics worry about compliance costs and unintended effects on startups and open-source projects.

How the AI Act works

The law classifies AI by risk level. Obligations increase with potential impact on people and society.

- Unacceptable risk: Certain uses are banned. These include social scoring by public authorities and manipulative systems that exploit vulnerabilities. There are narrow exceptions for public security.

- High-risk systems: Tools used in areas like hiring, credit scoring, medical devices, critical infrastructure, and law enforcement face strict requirements. Providers must meet standards on data governance, documentation, accuracy, human oversight, cybersecurity, and post-market monitoring.

- Limited risk: Systems such as chatbots and AI that generates synthetic media must meet transparency obligations. Users should be informed they are interacting with AI or viewing AI-generated content.

- Minimal risk: Most AI, including spam filters and video game AI, can be used with no new obligations.

The Act also creates specific duties for general-purpose AI (GPAI), the large models that can be adapted for many tasks. Providers must disclose technical details and training data summaries, address copyright safeguards, and share information with downstream developers. For very capable models that pose “systemic risk,” the law anticipates more robust testing, adversarial evaluation, and incident reporting.

When the rules take effect

Application is phased. Bans on unacceptable-risk uses apply first, months after entry into force. Transparency duties for limited-risk systems and GPAI follow. The most demanding obligations for high-risk systems arrive later, over a two- to three-year period. This staging is meant to give companies time to adjust, build controls, and certify systems before enforcement escalates.

Penalties can be significant. For the most severe violations, fines can reach up to €35 million or 7% of global annual turnover, whichever is higher. Lower tiers apply to less serious breaches and for providing incorrect or misleading information to regulators.

What changes for companies and developers

Organizations building or deploying AI in the EU will need to map their systems against the law’s risk categories. For high-risk tools, they will also need to implement compliance programs tied to technical standards and to keep records for audits. Large AI providers will be expected to support downstream users with documentation and guidance.

Compliance teams describe a shift toward practices already seen in safety-critical industries:

- Model governance: Clear accountability, roles, and approvals for AI lifecycle decisions.

- Data quality and bias management: Documented datasets, testing for representativeness, and mitigation plans.

- Technical robustness: Pre-deployment validation, red-teaming, and ongoing monitoring for drift and security.

- Human oversight: Procedures to review, override, or halt automated decisions.

- Transparency: User disclosures, system capability statements, and incident reporting.

Some obligations will be operationalized through harmonized European standards. Companies that follow those standards can more easily demonstrate conformity. Small firms may use sandboxes run by national authorities to test systems under supervision before bringing them to market.

Open-source and research carve-outs

The final text includes provisions to support research and innovation. Free and open-source AI components used for research and non-commercial purposes receive lighter treatment. Obligations focus on providers who place systems on the market or put them into service. Policymakers say this is intended to protect collaborative development while keeping guardrails for high-risk uses.

Global context: a patchwork of rules

The EU is not acting alone. Other governments are moving, though approaches differ. The OECD AI Principles, adopted in 2019, remain a reference point. They state that “AI should benefit people and planet by driving inclusive growth, sustainable development and well-being.” In the United States, a 2023 White House executive order emphasized the need for “safe, secure, and trustworthy” AI, and directed agencies to develop standards and testing. The U.K. held a global summit on frontier model safety and issued a pro-innovation framework. G7 countries backed voluntary codes for advanced model developers.

Industry is responding with governance tools and evaluations. The U.S. National Institute of Standards and Technology released a voluntary AI Risk Management Framework. Companies are building content provenance using emerging standards to help label synthetic media. Many large model providers publish system cards and disclose known limitations.

Supporters and critics

Backers argue the AI Act will align innovation with Europe’s rights-based approach. They say clear rules can reduce uncertainty, support cross-border trade, and avoid a race to the bottom. Consumer and civil rights groups welcome bans on intrusive surveillance practices. Health and financial regulators view the framework as an extension of existing safety and compliance regimes.

Business groups caution that costs could be high, especially for firms deploying high-risk systems across multiple markets. Open-source advocates warn that documentation and liability expectations could chill collaborative development if applied too broadly. Some academics note that rapidly evolving general-purpose models may outpace certification processes. They urge agile updates, realistic technical expectations, and strong coordination with international partners.

What to watch next

- Standards and guidance: Technical standards will translate legal duties into practical controls. Clarity on high-risk use cases and GPAI thresholds will shape compliance scope.

- Enforcement capacity: National authorities will need expertise to supervise complex systems. Resource constraints could affect consistency across the bloc.

- Interaction with existing laws: Expect overlap with product safety, medical device rules, financial services regulations, and data protection law.

- Developers’ playbooks: Providers may expand model documentation, evaluations, and safeguards to meet EU expectations and preempt similar rules elsewhere.

- Global ripple effects: Trading partners may align on parts of the EU model. Others may prioritize innovation flexibility. Companies will navigate a growing patchwork.

The AI Act is not the end of the policy story. Legislators and regulators will continue to update guidance as technology evolves. For now, Europe’s gamble is clear: set common rules, phase them in, and force the hardest conversations about risk into the open. Whether that delivers safer systems without slowing useful progress will be tested in the next few years.