EU AI Act begins: What changes for tech now

Europe’s new AI rulebook starts to bite

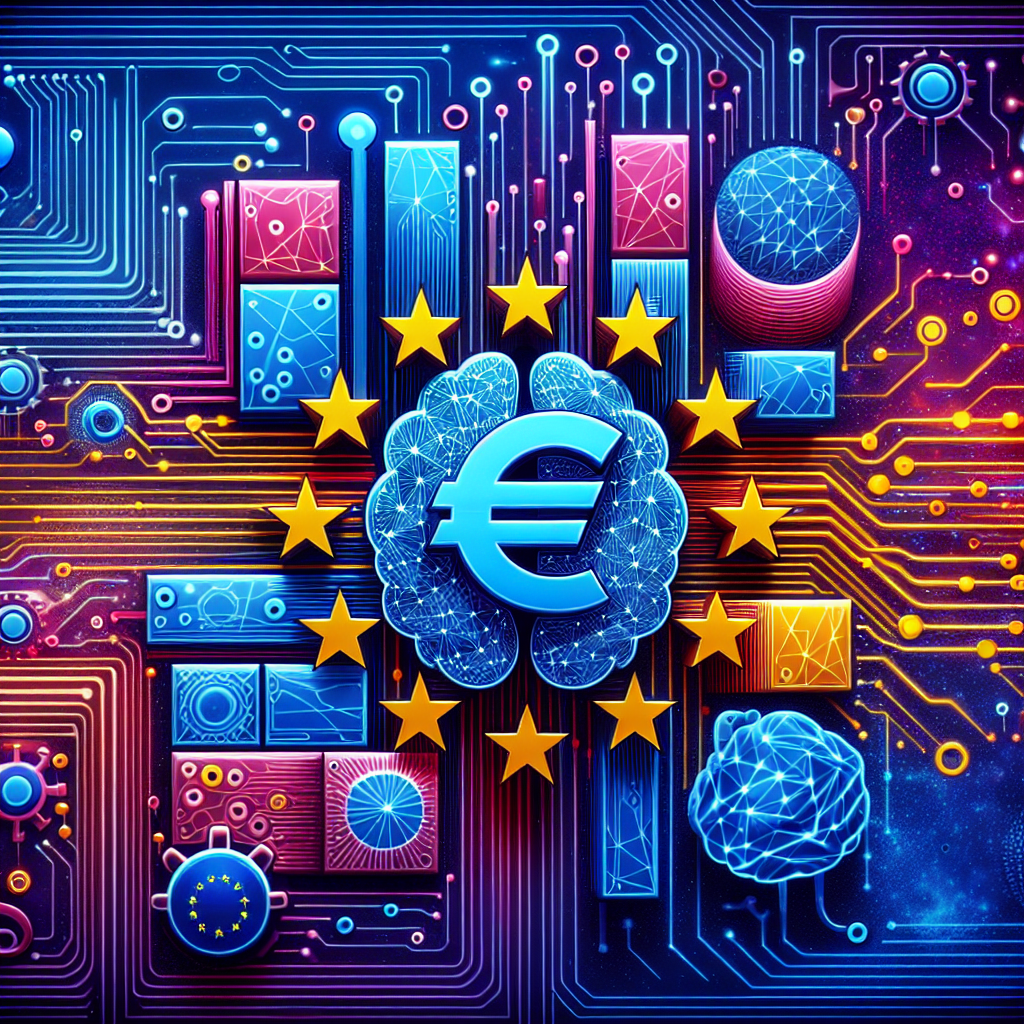

Europe’s landmark Artificial Intelligence Act is moving from text to practice. The law, adopted in 2024 after years of debate, ushers in a risk-based framework that will apply in phases over the next several years. The European Commission describes it as “the world’s first comprehensive AI rulebook.” Its focus is simple in principle: the higher the risk posed by an AI system, the stricter the obligations.

The rollout has immediate and longer-term implications for tech companies, public agencies, and startups. Some bans take effect first, followed by layered requirements for “high-risk” uses, and new duties for developers of general-purpose and frontier models. National regulators and a new EU AI Office are gearing up to translate the law into day-to-day oversight.

What the law does

The AI Act sorts systems into tiers based on potential harm to safety, fundamental rights, and the rule of law. It prohibits certain practices outright, such as public authority “social scoring,” exploitative manipulation of vulnerable people, and many uses of “real-time remote biometric identification” in public spaces, with narrow law-enforcement exceptions. The most demanding rules target “high-risk” systems, such as those used in medical devices, hiring, education, critical infrastructure, and essential public services. These systems must meet requirements for risk management, data governance, documentation, testing, and human oversight.

General-purpose AI (GPAI) and so‑called frontier models also come into scope. Developers face duties around transparency, model evaluation, cybersecurity, and reporting of serious incidents. Content provenance and labeling are part of the toolkit. Similar language appears in a 2023 U.S. executive order that calls for “safe, secure, and trustworthy AI,” signaling growing alignment among advanced economies.

Key obligations at a glance

- Prohibited practices: bans on a narrow set of uses deemed unacceptable, including public-sector social scoring and certain biometric surveillance.

- High-risk compliance: risk management, high-quality training data, technical documentation, post-market monitoring, and human oversight before deployment.

- Transparency: clear user disclosures for AI systems that interact with people, detect emotions, or generate content, including labeling where required.

- General-purpose AI: technical documentation, safety policies, cybersecurity safeguards, and model evaluations proportionate to scale and capability.

- Enforcement architecture: coordination by the EU AI Office, with national authorities conducting market surveillance and imposing penalties for violations.

Industry prepares for a phased timeline

Compliance will not happen overnight. The law staggers obligations to give developers and deployers time to adapt. Companies are building internal governance programs, mapping where AI is used, and documenting datasets and model behavior. Many are borrowing from established standards, including the U.S. National Institute of Standards and Technology’s AI Risk Management Framework, which emphasizes an iterative cycle of measurement and improvement. Corporate boards are asking for dashboards that surface model risks alongside business metrics.

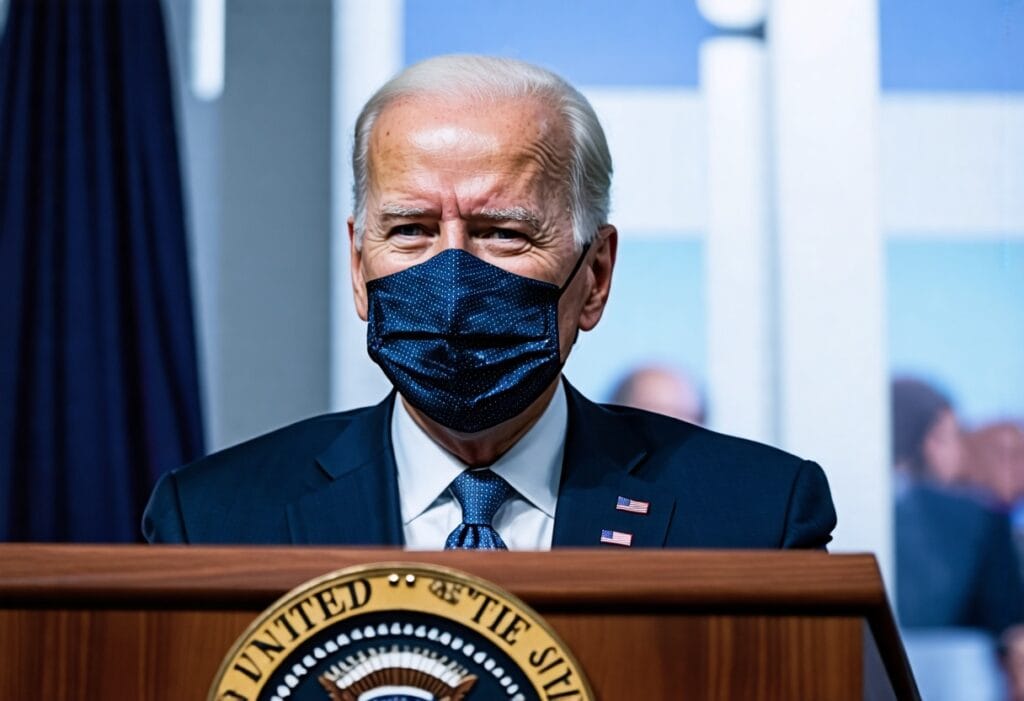

Multinational firms face a patchwork. The EU approach is the most comprehensive so far, but other jurisdictions are moving. The United Kingdom’s 2023 AI Safety Summit produced the Bletchley Declaration, committing signatories to the “safe development of AI technologies.” In the United States, federal guidance and sectoral rules are expanding. International bodies, including the OECD, continue to promote principles such as “human-centered values,” “robustness, security and safety,” and “accountability.”

Supporters, skeptics, and the balance to strike

Backers say the AI Act sets guardrails without freezing innovation. They argue that minimal baseline rules reduce uncertainty and can boost public trust. Consumer groups also point to strengthened redress mechanisms, audits, and the right to meaningful human review in sensitive decisions.

Critics worry about compliance costs and unintended consequences for open research and startups. Small developers may struggle with paperwork and monitoring obligations if they build tools that end up in high-risk contexts. Open-source communities question how documentation and incident-reporting rules will apply in practice. There is also debate over watermarking and content provenance, especially for audio and video. Advocates say provenance can help curb deception; artists and newsrooms want clarity on fair use and compensation for training data.

Enforcers must reconcile these tensions. The EU AI Office will issue guidance, coordinate codes of practice, and supervise general-purpose model duties. National authorities will need resources and technical expertise to conduct inspections and evaluate documentation. Regulators are signaling a cooperative approach early on, focusing on education and corrective actions before heavy penalties.

What organizations should do now

- Inventory AI systems: maintain a register of models, use cases, and business owners; flag potential high-risk applications.

- Classify and gap-assess: determine risk tiers and compare current controls to expected obligations; plan remediation.

- Strengthen data governance: document training datasets, sources, and licenses; address bias and representativeness; record data lineage.

- Build evaluation pipelines: adopt systematic pre-deployment and post-deployment testing for accuracy, robustness, and fairness; log incidents.

- Enable human oversight: define when and how people can review, override, and appeal automated decisions.

- Improve transparency: prepare user-facing disclosures and content provenance signals for generative features.

- Align with standards: leverage existing frameworks and sector rules to avoid duplication and audit fatigue.

Global ripple effects

Europe’s decision often travels. The General Data Protection Regulation reshaped global privacy practices; the AI Act could repeat that pattern. Vendors may ship “EU-compliant” models worldwide to simplify operations. Academic and civil-society researchers are likely to scrutinize how firms implement risk controls and publish safety reports. Lawmakers elsewhere are watching for early evidence on enforcement, innovation, and competition.

There is no single blueprint. The United States relies more on agency guidance and liability, while the United Kingdom coordinates through sector regulators. Still, the policy vocabulary is converging: testing before deployment, transparency about capabilities and limits, and accountability for harms. As one European official put it when the law cleared its final vote, the goal is to keep AI “trustworthy and human-centric,” while letting research and business thrive.

The road ahead

The next year will be about translation—turning legal text into engineering checklists and product requirements. Expect iterative guidance, test cases, and course corrections as authorities, companies, and researchers compare notes. The stakes are high: AI is moving deeper into healthcare, finance, education, and public services. The promise is large, and so are the risks. With the AI Act’s phased start, Europe is betting that clear rules can steer the technology toward broad benefit. Whether the approach becomes a global template will depend on results measured not only in innovation metrics, but in safety, quality, and public trust.

For now, one principle spans borders. As the U.S. executive order framed it, AI should be “safe, secure, and trustworthy.” Europe’s new law puts that aspiration to the test.