EU AI Act Takes Effect: What Changes Now

Europe has entered a new era of technology regulation. The European Union’s Artificial Intelligence Act has taken effect, launching a phased rollout that will reshape how AI is built and used across the bloc. Policymakers call it the world’s first comprehensive AI law. The rules aim to lower risk, boost trust, and keep innovation alive. Companies around the world that sell or deploy AI in the EU will feel the impact.

What the law does

The AI Act follows a risk-based approach. Obligations increase with the potential harm an AI system can cause. The law groups systems into four categories.

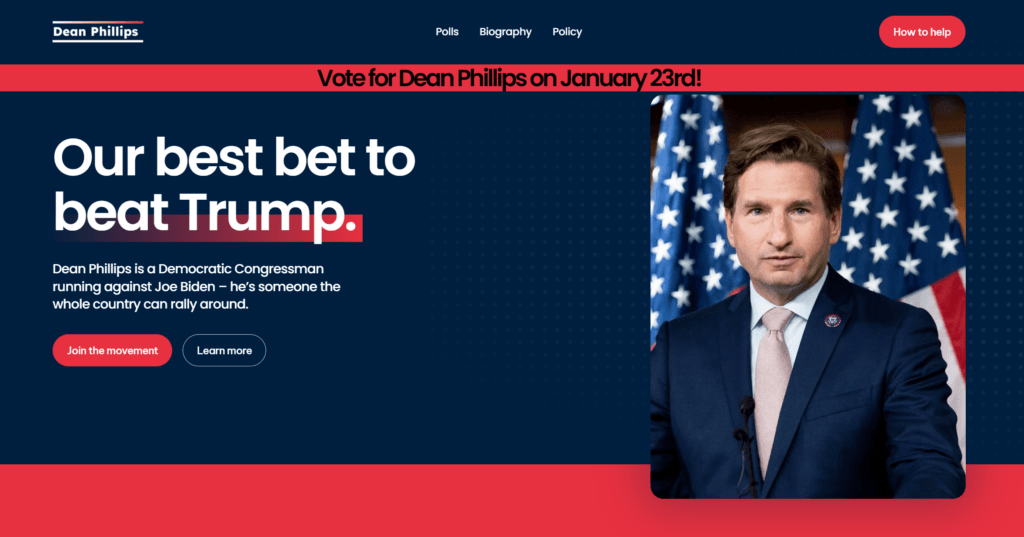

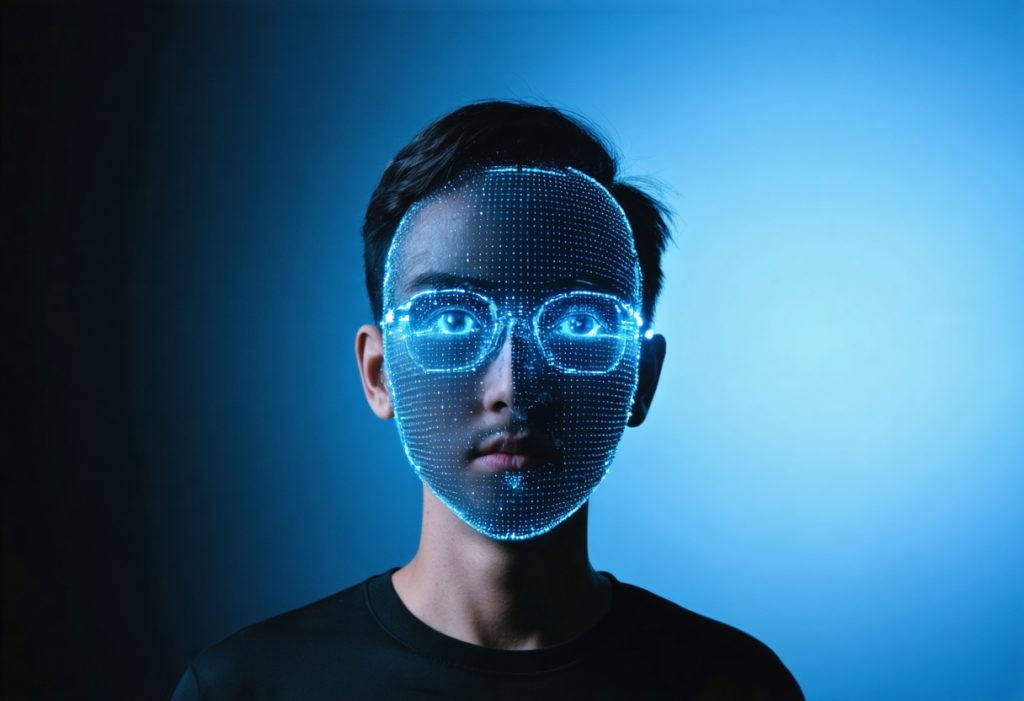

- Unacceptable risk systems are banned. These include AI that manipulates vulnerable people, social scoring by public authorities, and certain biometric categorization. Real-time remote biometric identification in public spaces for law enforcement is broadly prohibited, with narrow exceptions defined in the law and subject to strict safeguards.

- High-risk systems face strict rules. They include AI used in critical infrastructure, education, employment, essential public and private services, law enforcement, migration and border control, and the administration of justice.

- Limited risk systems must be transparent. Users should be told when they interact with AI, and synthetic content should be labeled so people are not misled.

- Minimal risk systems face no new obligations under the Act.

For high-risk systems, providers must put in place risk management, high-quality training data practices, human oversight, robust cybersecurity, and detailed documentation. They will need conformity assessments, post-market monitoring, and a route for incident reporting. Products that meet the rules can carry a CE mark, just like other regulated technologies in the EU.

The European Commission has described the law as historic. “The AI Act is the first comprehensive law on AI worldwide,” the Commission says in its communications on the legislation (European Commission, 2024).

Generative and general-purpose AI

One of the most debated parts covers general-purpose AI (GPAI), including large language models. Providers of such models face transparency duties. They must prepare technical documentation for downstream deployers, support information sharing with regulators, and publish a summary of copyrighted data used for training. The final text refers to “a sufficiently detailed summary” to help rightsholders understand use without forcing disclosure of trade secrets.

Very capable models that pose systemic risk will face additional obligations, such as safety evaluations, incident reporting, and reinforced cybersecurity practices. The European Commission has created an AI Office to coordinate supervision of GPAI across member states and to support consistent enforcement.

Key dates and penalties

The law took effect in 2024 and rolls out in stages to give organizations time to adapt.

- 6 months after entry into force: bans on unacceptable-risk systems start to apply.

- 9 months: voluntary codes of practice for GPAI and preparatory measures kick in.

- 12 months: core rules for general-purpose AI providers take effect.

- 24 months: most obligations for high-risk AI systems apply.

- 36 months: some sector-specific high-risk uses face longer timelines to comply.

Penalties are significant. Fines can reach up to €35 million or 7% of global annual turnover for the most serious violations, such as banned practices. Other breaches can draw fines of up to €15 million or 3%, and supplying incorrect information can lead to penalties of up to €7.5 million or 1%. National regulators will supervise compliance, coordinated by EU-level bodies.

Why it matters for business

The EU market is large, and the rules have extraterritorial effects. Non-EU providers must comply if they place AI systems on the EU market or if their systems affect people in the EU. This is a classic example of the “Brussels effect,” where EU standards influence global practices.

Many firms plan to align compliance with established frameworks. The U.S. National Institute of Standards and Technology recommends organizations “govern, map, measure, and manage” AI risks (NIST AI RMF 1.0, 2023). The international standard ISO/IEC 42001 sets up a management system for AI. These tools can help companies build the documentation and controls the EU will expect to see.

Industry and civil society response

Technology companies welcome a single EU rulebook but worry about cost and complexity, especially for smaller firms. Startups say they need clarity on how to label, document, and test models without slowing their release cycles. Consumer and digital rights groups support bans on social scoring and stronger oversight of biometric systems. They also press for meaningful transparency for generative content and effective remedies for users.

Global governance efforts are converging on similar goals. A 2024 United Nations resolution urges the development of “safe, secure and trustworthy” AI systems (UN General Assembly, 2024). The G7’s Hiroshima process has promoted risk-based practices for advanced models. These initiatives do not impose binding rules, but they point in the same direction as the EU law.

What organizations should do now

- Inventory AI systems. Identify where AI is in products and internal processes. Classify uses by risk level under the Act.

- Gap analysis. Compare current controls to EU requirements, NIST AI RMF, and ISO/IEC 42001. Prioritize high-risk and GPAI-related gaps.

- Data governance. Strengthen data quality, provenance checks, and copyright screening. Plan for training data documentation.

- Technical documentation. Build model cards, system logs, and evaluation records. Prepare conformity assessment materials for high-risk systems.

- Human oversight. Define clear intervention points. Train staff on escalation and incident reporting.

- Vendor and contract updates. Flow down obligations to suppliers and downstream deployers. Specify audit rights and incident duties.

- Labeling and user disclosures. Implement clear notices for AI interactions and synthetic media.

- Testing and red-teaming. Evaluate safety, robustness, bias, and cybersecurity. Document results and mitigations.

What it means for consumers

People should see more transparency about when they are dealing with AI. Synthetic media should be labeled, helping users spot deepfakes. High-risk systems must build in human oversight. There will be new channels to report problems and seek redress. National authorities can order fixes and impose fines if providers break the rules.

The road ahead

Much will depend on implementation. The Commission and national regulators will issue guidance, templates, and lists that define high-risk use cases in more detail. Test standards and reference benchmarks will evolve. Companies will push for interoperability between EU requirements and frameworks used in other regions. Policymakers will face pressure to keep the rules current as AI capabilities advance.

The EU has set a marker. Supporters say clearer rules will increase trust and encourage adoption. Critics warn about compliance costs and the risk of locking in today’s methods. Both points carry weight. What happens over the next two years—how firms adapt, how regulators enforce, and how the market responds—will decide whether the AI Act becomes a model for the world or a cautionary tale.